A specific person, skeptical of evolution, asked for a plausible explanation to the question "How did flight evolve?"

There are layers of answers to this question, and others like it. I will start with the general and move toward the specific.

1) A missing piece of the story does not sink the theory.

Let me explain by way of analogy. A detective is investigating a murder. The victim was murdered in front of a dumpster in an alley with a single shot from a specific .357 magnum revolver. Despite public controversy surrounding the matter, the detective knows that this is the murder location because all evidence indicates that the victim was shot here:

- There is a .357 magnum sized bullet hole, corresponding damage, and the characteristic burns and other marks (I won't get graphic) associated with a gunshot wound of this caliber, in the victim's skull.

- A .357 magnum bullet, as well as blood and other biological material from the victim's skull, were found embedded in the front of the dumpster. Ballistics matches the bullet to a .357 magnum revolver which

- Was found in the dumpster, with signs of having been fired, as well as blood splatter from the victim.

- There is a huge amount of the victim's blood, almost all of it, in the dumpster.

- All blood at the scene matches the victim.

...and so on. It's airtight, the killing happened here.

However,

-The body was found on the roof of a nearby hotel.

-There is very little blood in the vicinity of the body, nor any other signs that someone was murdered here, apart from the body.

-The blood, which has settled and rigidified due to livermortis, is in the victim's back even though the victim is facedown.

-Going through the security tapes for the hotel, which are all date/time stamped and appear to cover all entrances and exits to the hotel, there does not appear to be anyone lugging a body up to the roof at any point.

-The body does not show additional damage that might be expected during careless transport.

Now, the detective has every reason to believe that the victim was murdered in the alley, in front of a dumpster, by a person with the .357 magnum they found in the dumpster, and that the body was thrown in the dumpster where it drained of blood and was later moved to the nearby roof. He has no idea how the body was later moved to the roof. He has no idea why. He can't explain how someone could have gotten the body up there without showing up on the security footage.

All of the ideas he can think of might seem implausible, such as:

- The body was moved by helicopter?

- The killer later wrapped the body in plastic and carefully hoisted up to the roof?

- The security tapes have been expertly tampered with?

- The body was cleverly hidden inside of luggage when it was moved?

None of these may seem satisfying to the detective, but it doesn't matter, he doesn't need to know the details of

how the body got moved to the roof to know that this is what happened. The victim could not possibly have been killed on the roof, because the evidence does not match that scenario. The evidence is that this person was shot in front of the dumpster in the alley. There's a huge hole in his narrative, but it doesn't change the fact that the victim was murdered in the alley, and not on the roof. Nothing else explains the evidence; there are no other plausible options. Whatever questions he might have about who, or how, or why, the location of death is a fact.

People can say foolish things like

"There's a body on the roof and you think he wasn't killed there? Like someone is really gonna carry a body to the roof. Derp derp. They even checked the security footage, and the body was miraculously not damaged during the "move". There's proof positive that no one moved this body." (I'll spare you the caps lock.)

These people might be convinced, and might convince others. They might start www.HeWasKilledOnTheRoof.com and generate a huge following, and have YouTube videos with 2.3 million views, and memes mocking the detective, but

they still have no idea what they're talking about. They are amateur armchair detectives, they are flatly wrong, and the fact that no police or other serious investigators put stock in their version should indicate this to them, but they will prefer instead to assume some vast conspiracy to defile the truth in the name of some imagined agenda.

And so it is with Theory of Evolution. There are countless species on the Earth, and we do not need to know the details of how every feature of every species evolved to consider evolution an indisputable fact. Evolution is fact because there is no other explanation for the

evidence. Even if scientists had no idea whatsoever how flying might have evolved, that would not disprove evolution, nor even cast any doubt upon it.

2) The "unbelievability" of a particular theory to a non-expert means nothing.

As do all of the arguments that sound convincing to non-experts, but have not swayed experts. I want to be clear that I am not invoking an

Appeal to Authority Logical Fallacy here. It does not follow that evolution is necessarily true because expert scientists believe it.

However, a person who is not personally an expert in the subject is also not qualified to dismiss expert opinion on a matter. This is not to say that a non-expert couldn't uncover evidence or think of an argument that would overturn an established matter, but if experts have seen that evidence and heard that argument, and are unimpressed, and are still satisfied that the theory holds true, then there is no credible reason for a non-expert to believe otherwise.

It is the fool who prefers the word of the non-expert, or to rejects a matter simply because it is not personally understood. (This would be the

Personal Incredulity Fallacy). It is, of course, not completely

impossible that the non-expert is actually correct, but it's

very unlikely, and if you go through life believing non-experts on all matters you're going to live an existence of ignorance. This is the realm of conspiracy theorists, snake oil purchasers, perpetual motion machine builders, seekers of Tesla's "free electricity", and so on. Don't fall for it. All those PhDs aren't stupid, or missing some obvious thing that you read on the internet.

3) The actual answer to your question

Is that the evolution of flight is an area under investigation, and there are several schools of thought. You can read some about it here in

this article, or

this one, or

this one which I found by laboriously... no, wait. I just googled "what good is half a wing evolution". Answers about evolution are all over the internet. Seriously, try it sometime. You could also read

this book, or, if you think you'd be able to read Dawkins without bursting into flames,

this one.

4) Wash, Rinse, Repeat?

Most Creationists, after having one doubt addressed, will simply move to the next one. This is generally because the questions are not being asked in good faith, but in an attempt to find the "gotcha" problem that will stump the evolutionist and demonstrate how wrong they are. (Oh, the irony.)

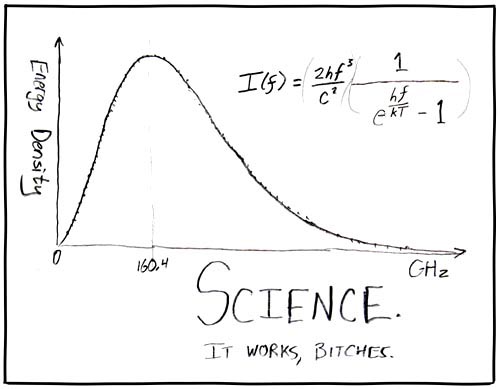

Please don't do this. Seriously. I totally understand if evolution seems completely and utterly not-plausible to you. It's a pretty mind-blowing revelation, but look, so is Quantum, and Quantum is just true. I hate Quantum, it sounds like total nonsense, but apparently the universe doesn't care how I feel because Quantum is real. If you still have doubts about a scientific theory, see points 1 & 2. Google it, read some books, study the subject. If you aren't convinced by popular science write-ups and aren't satisfied with accepting expert opinion, then become a genuine expert yourself (Hint: this involves graduate work at a university). Only then will any clear-thinking person see your disbelief of an established scientific theory as anything other than an unfortunate misunderstanding on your part.